Dados Raster¶

|

Objectivos: |

Compreender o que são dados raster (matriciais) e como podem ser usados num SIG. |

Palavras-chave: |

Raster, Pixel, Detecção Remota, Satélite, Imagem, Georreferenciação |

Resumo¶

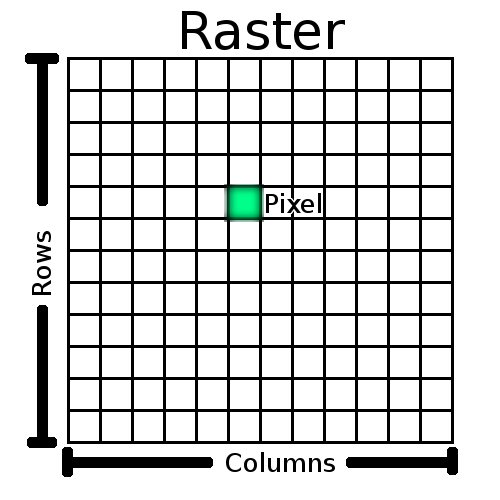

Nos tópicos anteriores abordámos com mais detalhe os dados vectoriais. Enquanto elementos vectoriais usam geometria (pontos, linhas e polígonos) para representar o mundo real, a informação matricial toma uma abordagem diferente. Rasters são constituídos por uma matriz de pixeis (também chamados células), cada contendo um valor que representa as condições para a área coberta por essa célula (ver figure_raster). Neste tópico vamos abordar em detalhe os dados matriciais, quando são úteis e quando fazem mais sentido do que usar dados vectoriais.

Figure Raster 1:

Dados raster em detalhe¶

Dados raster são usados numa aplicação SIG quando queremos visualizar informação que é contínua através de uma área e não pode ser facilmente dividida em elementos vectoriais. Quando fizemos a introdução aos dados vectoriais mostrámos a imagem na figure_landscape. Elementos do tipo ponto, linha e polígono funcionam bem para representar algumas características da paisagem, tais como árvore, estradas e delimitações de edifícios. Outras características numa paisagem podem ser mais difíceis de representar usando vectores. Por exemplo, as áreas verdes mostradas podem ter muitas variações em cor e densidade de cobertura. Seria bastante fácil criar um único polígono rodeando cada área verde, mas muita da informação sobre a área verde seria perdida no processo de simplificar essas características num único polígono. Isto sucede porque quando se atribuem valores de atributos a um elemento vectorial, estes aplicam-se a todo o elemento vectorial, por isso vectores não se adequam bem à representação de características que não são homogéneas (totalmente iguais) em toda a sua extensão. Outra abordagem que se pode tomar é digitalizar todas as pequenas variações de cor e de cobertura como um polígono individual. O problema com esta abordagem é que exigirá uma enorme quantidade de trabalho para criar uma boa cobertura vectorial.

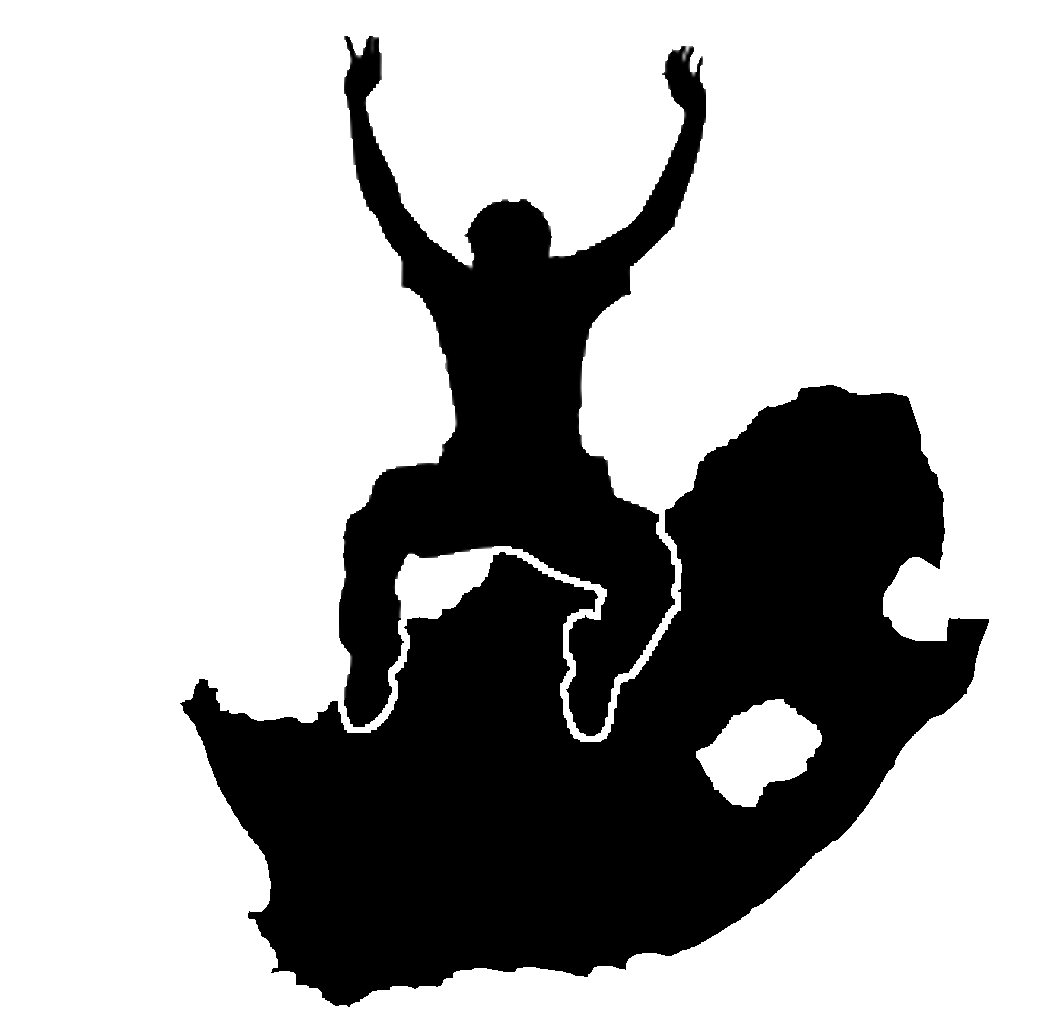

Figure Landscape 1:

Algumas características numa paisagem são facilmente representadas como pontos, linhas e polígonos (e.g. árvores, estradas, casas). Noutros casos pode ser difícil. Por exemplo, como representaria uma área de pastagens? Como polígonos? O que fazer às variações de cor que consegue ver nas pastagens? Quando está a tentar representar grandes áreas com valores que mudam continuamente, os dados raster podem ser uma melhor escolha.

Usar dados matriciais é a solução para estes problemas. Muitos utilizadores usam dados raster como um fundo a usar por detrás de camadas vectoriais, de forma a fornecer mais significado à informação vectorial. O olho humano é muito bom a interpretar imagens e por isso usar uma imagem por detrás de camadas vectoriais resulta em mapas com muito mais significado. Dados matriciais são não só bons para imagens que ilustram a superfície do mundo real (e.g. imagens de satélite e fotografias aéreas), como também são bons a representar ideias mais abstractas. Por exemplo, rasters podem ser usados para mostrar tendências de precipitação através de uma área, ou para ilustrar o risco de incêncio numa paisagem. Neste tipo de aplicações, cada célula na matriz representa um valor diferente, e.g. risco de incêndio numa escala de 1 a dez.

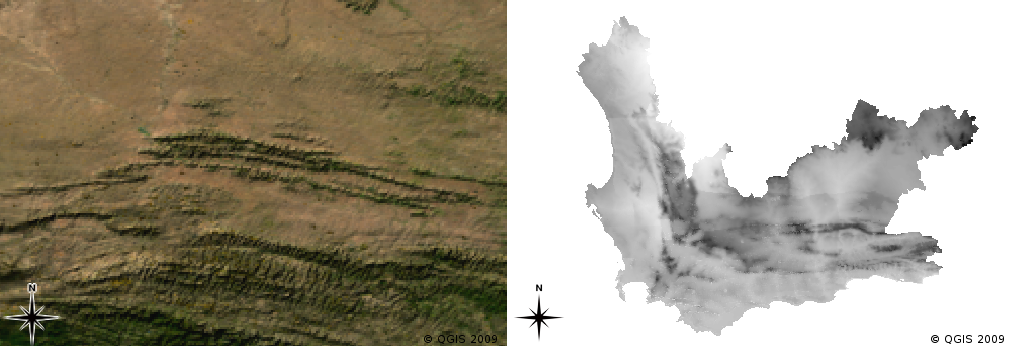

Um exemplo que mostra as diferenças entre uma imagem obtido de um satélite ou uma que mostra valores calculados pode ser visto na figure_raster_types.

Figure Raster Types 1:

Imagens raster de cor verdadeira (esquerda) são úteis porque fornecem muito detalhe que é difícil de capturar em vectores mas são fáceis de ver quando se olha para a imagem raster. Dados matriciais podem ser também dados não-fotográficos, tais como a camada matricial mostrada à direita e que representa a temperatura mínima média calculada para a província Western Cape para o mês de Março.

Georreferenciação¶

Georreferenciação é o processo de definir exactamente onde na superfície da terra foi criada uma imagem ou conjunto de dados matriciais. Este informação posicional é armazenada com a versão digital da fotografia aérea. Quando a aplicação SIG abre a foto, utiliza a informação posicional para assegurar que a foto surge no local correcto no mapa. Normalmente, esta informação posicional consiste de uma coordenada para o pixel no topo superior esquerdo da imagem, o tamanho de cada pixel na direcção X, o tamanho de cada pixel na direcção Y, e o valor (se existir) da rotação da imagem. Com estes valores, a aplicação SIG pode assegurar que a informação raster é visualizada no local correcto. A informação de georreferenciação de um raster é muitas vezes fornecida num pequeno ficheiro de texto que acompanha o raster.

Fontes de dados raster¶

Dados matriciais podem ser obtidos de várias formas. Duas das mais comuns são fotografia aérea e imagens de satélite. Na fotografia aérea, uma aeronave voa sobre uma área transportando uma câmara. As fotografias são depois importadas para um computador e georreferenciadas. A imagem de satélite é criada quando satélites que orbitam a terra direccionam câmaras digitais especiais para a terra e obtém uma imagem da área da terra sobre a qual passam. Uma vez obtida a imagem, esta é enviada para a terra usando sinais de rádio para estações de recepção especiais tais como as mostradas na figure_csir_station. O processo de captura de dados matriciais a partir uma aeronave ou satélite é denominado por detecção remota.

Figure CSIR Station 1:

The CSIR Satellite Applications Center at Hartebeeshoek near Johannesburg. Special antennae track satellites as they pass overhead and download images using radio waves.

Noutros casos, os dados raster podem ser computarizados. Por exemplo, uma companhia de seguros pode usar dados sobre incidentes criminais em relatórios policiais e criar mapas raster do país mostrando a susceptibilidade de incidência de crimes em cada área. Metereologistas (pessoas que estudam padrões do tempo) podem gerar mapas raster de nível provincial mostrando a temperatura média, queda de chuvas e direção do vento usando dados colhidos em estações metereológicas (veja a figura_estação_csir). Nestes casos, posteriormente eles usam técnicas de análise raster como interpolação (Descritas no Tópico :ref:´`análise_espacial`).

Sometimes raster data are created from vector data because the data owners want to share the data in an easy to use format. For example, a company with road, rail, cadastral and other vector datasets may choose to generate a raster version of these datasets so that employees can view these datasets in a web browser. This is normally only useful if the attributes, that users need to be aware of, can be represented on the map with labels or symbology. If the user needs to look at the attribute table for the data, providing it in raster format could be a bad choice because raster layers do not usually have any attribute data associated with them.

Resolução Espacial¶

Every raster layer in a GIS has pixels (cells) of a fixed size that determine its spatial resolution. This becomes apparent when you look at an image at a small scale (see figure_raster_small_scale) and then zoom in to a large scale (see figure_raster_large_scale).

Figure Raster Scale 1:

Figure Raster Scale 2:

Several factors determine the spatial resolution of an image. For remote sensing data, spatial resolution is usually determined by the capabilities of the sensor used to take an image. For example SPOT5 satellites can take images where each pixel is 10 m x 10 m. Other satellites, for example MODIS take images only at 500 m x 500 m per pixel. In aerial photography, pixel sizes of 50 cm x 50 cm are not uncommon. Images with a pixel size covering a small area are called ‘high resolution‘ images because it is possible to make out a high degree of detail in the image. Images with a pixel size covering a large area are called ‘low resolution‘ images because the amount of detail the images show is low.

In raster data that is computed by spatial analysis (such as the rainfall map we mentioned earlier), the spatial density of information used to create the raster will usually determine the spatial resolution. For example if you want to create a high resolution average rainfall map, you would ideally need many weather stations in close proximity to each other.

One of the main things to be aware of with rasters captured at a high spatial resolution is storage requirements. Think of a raster that is 3 x 3 pixels, each of which contains a number representing average rainfall. To store all the information contained in the raster, you will need to store 9 numbers in the computer’s memory. Now imagine you want to have a raster layer for the whole of South Africa with pixels of 1 km x 1 km. South Africa is around 1,219,090 km 2. Which means your computer would need to store over a million numbers on its hard disk in order to hold all of the information. Making the pixel size smaller would greatly increase the amount of storage needed.

Sometimes using a low spatial resolution is useful when you want to work with a large area and are not interested in looking at any one area in a lot of detail. The cloud maps you see on the weather report, are an example of this –– it’s useful to see the clouds across the whole country. Zooming in to one particular cloud in high resolution will not tell you very much about the upcoming weather!

On the other hand, using low resolution raster data can be problematic if you are interested in a small region because you probably won’t be able to make out any individual features from the image.

Resolução Espectral¶

If you take a colour photograph with a digital camera or camera on a cellphone, the camera uses electronic sensors to detect red, green and blue light. When the picture is displayed on a screen or printed out, the red, green and blue (RGB) information is combined to show you an image that your eyes can interpret. While the information is still in digital format though, this RGB information is stored in separate colour bands.

Whilst our eyes can only see RGB wavelengths, the electronic sensors in cameras are able to detect wavelengths that our eyes cannot. Of course in a hand held camera it probably doesn’t make sense to record information from the non-visible parts of the spectrum since most people just want to look at pictures of their dog or what have you. Raster images that include data for non-visible parts of the light spectrum are often referred to as multi-spectral images. In GIS recording the non-visible parts of the spectrum can be very useful. For example, measuring infra-red light can be useful in identifying water bodies.

Because having images containing multiple bands of light is so useful in GIS, raster data are often provided as multi-band images. Each band in the image is like a separate layer. The GIS will combine three of the bands and show them as red, green and blue so that the human eye can see them. The number of bands in a raster image is referred to as its spectral resolution.

If an image consists of only one band, it is often called a grayscale image. With grayscale images, you can apply false colouring to make the differences in values in the pixels more obvious. Images with false colouring applied are often referred to as pseudocolour images.

Conversão Raster para Vector¶

In our discussion of vector data, we explained that often raster data are used as a backdrop layer, which is then used as a base from which vector features can be digitised.

Another approach is to use advanced computer programs to automatically extract vector features from images. Some features such as roads show in an image as a sudden change of colour from neighbouring pixels. The computer program looks for such colour changes and creates vector features as a result. This kind of functionality is normally only available in very specialised (and often expensive) GIS software.

Conversão Vector para Raster¶

Sometimes it is useful to convert vector data into raster data. One side effect of this is that attribute data (that is attributes associated with the original vector data) will be lost when the conversion takes place. Having vectors converted to raster format can be useful though when you want to give GIS data to non GIS users. With the simpler raster formats, the person you give the raster image to can simply view it as an image on their computer without needing any special GIS software.

Análise Raster¶

There are a great many analytical tools that can be run on raster data which cannot be used with vector data. For example, rasters can be used to model water flow over the land surface. This information can be used to calculate where watersheds and stream networks exist, based on the terrain.

Raster data are also often used in agriculture and forestry to manage crop production. For example with a satellite image of a farmer’s lands, you can identify areas where the plants are growing poorly and then use that information to apply more fertilizer on the affected areas only. Foresters use raster data to estimate how much timber can be harvested from an area.

Raster data is also very important for disaster management. Analysis of Digital Elevation Models (a kind of raster where each pixel contains the height above sea level) can then be used to identify areas that are likely to be flooded. This can then be used to target rescue and relief efforts to areas where it is needed the most.

Common problems / things to be aware of¶

As we have already mentioned, high resolution raster data can require large amounts of computer storage.

What have we learned?¶

Let’s wrap up what we covered in this worksheet:

- Raster data are a grid of regularly sized pixels.

- Raster data are good for showing continually varying information.

- The size of pixels in a raster determines its spatial resolution.

- Raster images can contain one or more bands, each covering the same spatial area, but containing different information.

- When raster data contains bands from different parts of the electromagnetic spectrum, they are called multi-spectral images.

- Three of the bands of a multi-spectral image can be shown in the colours Red, Green and Blue so that we can see them.

- Images with a single band are called grayscale images.

- Single band, grayscale images can be shown in pseudocolour by the GIS.

- Raster images can consume a large amount of storage space.

Now you try!¶

Here are some ideas for you to try with your learners:

- Discuss with your learners in which situations you would use raster data and in which you would use vector data.

- Get your learners to create a raster map of your school by using A4 transparency sheets with grid lines drawn on them. Overlay the transparencies onto a toposheet or aerial photograph of your school. Now let each learner or group of learners colour in cells that represent a certain type of feature e.g. building, playground, sports field, trees, footpaths etc. When they are all finished, overlay all the sheets together and see if it makes a good raster map representation of your school. Which types of features worked well when represented as rasters? How did your choice in cell size affect your ability to represent different feature types?

Something to think about¶

If you don’t have a computer available, you can understand raster data using pen and paper. Draw a grid of squares onto a sheet of paper to represent your soccer field. Fill the grid in with numbers representing values for grass cover on your soccer field. If a patch is bare give the cell a value of 0. If the patch is mixed bare and covered, give it a value of 1. If an area is completely covered with grass, give it a value of 2. Now use pencil crayons to colour the cells based on their values. Colour cells with value 2 dark green. Value 1 should get coloured light green, and value 0 coloured in brown. When you finish, you should have a raster map of your soccer field!

Further reading¶

Book:

- Chang, Kang-Tsung (2006). Introduction to Geographic Information Systems. 3rd Edition. McGraw Hill. ISBN: 0070658986

- DeMers, Michael N. (2005). Fundamentals of Geographic Information Systems. 3rd Edition. Wiley. ISBN: 9814126195

Website: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/GIS#Raster

The QGIS User Guide also has more detailed information on working with raster data in QGIS.

What’s next?¶

In the section that follows we will take a closer look at topology to see how the relationship between vector features can be used to ensure the best data quality.